Washington, Oregon and British Columbia pledged to slash greenhouse gas emissions. In a decade full of big talk and some epic battles, they all failed.

With dozens of people killed by wildfires in the western U.S., millions of acres scorched, and choking smoke spreading far into British Columbia, Washington Gov. Jay Inslee lit up the news wires in September. “These are not just wildfires,” Inslee asserted at a press conference from Olympia, “these are climate fires.”

Two days later on George Stephanopoulos’ Sunday-morning ABC News talk show, the recent presidential candidate recounted a poignant visit to a town nearly wiped out by the fires. “The only moisture in Eastern Washington was the tears of people who have lost their homes,” said Inslee. “And now we have a blowtorch over our states in the West, which is climate change.”

Just days after his return to the national stage, however, the question in a Seattle courtroom was whether the state Inslee had run since 2013 should be sanctioned for helping to load and light that torch. On Thursday Sept. 17 an attorney representing Inslee and the entire apparatus of Washington state government stood to tell three masked judges behind a plexiglass shield that courts could not hold the state legally responsible for its part in the climate crisis: The part where it expanded highways. The part where it licensed power plants and factories to emit many tons of greenhouse gases. Where it set building standards that would keep residents’ stoves and furnaces and water heaters polluting the atmosphere for decades to come.

Washington Gov. Jay Inslee, center, pulls off his “100%” cap, standing for a goal of 100% clean electricity, after posing for a photo with supporters after signing climate protection legislation on May 7, 2019, in Seattle. As a first step toward getting fossil fuels out of electricity, the measure required utilities to stop burning coal by the end of 2025. Elaine Thompson/AP

Thick haze from the climate fires still clogged the air outside the appeals courtroom in downtown Seattle as Assistant Attorney General Chris Reitz offered his arguments. The panel of judges peppered him with questions and probed for logical holes.

“I have asthma,” interjected one of the judges, David Mann of the Washington Court of Appeals Division One. “So I have to stay inside, with the windows shut.”

“Why isn’t that affecting my life and my liberty?”

The events leading to this legal confrontation in Washington, years in the making, are akin to those that recently prompted similar battles in Oregon and British Columbia courtrooms — government action and inaction that has increasingly spurred legal actions around the globe. In the Washington case, as in those to the north and south, young people are suing to stop what they call a state-sanctioned degradation of their futures.

A rower glides across Lake Union through wildfire smoke that obscures the Seattle skyline, Friday, Sept. 11, 2020. Scientists say the increasingly common smoke incursions in the region are driven by climate change. Dan DeLong/InvestigateWest

One of the Washington plaintiffs is 20-year-old Seattleite Aji Piper, who has been suing the state and U.S. governments over climate’s impact on his life and liberty for five years. As Piper said in a 2018 TED Talk, he is fighting for humanity’s ability to “change places with another, see their plight, adapt, and make better choices.”

But the halting pace and limited progress amplifies the anxiety and anguish that the climate crisis represents for so many young people, he said.

“The worst for me as a plaintiff is when we’re just sitting nowhere and waiting,” Piper said in a Zoom interview after the court hearing.

“It’s frustrating,” agreed his attorney, Andrea Rodgers, from her adjacent Zoom picture box.

“Washington has been defending itself by saying, ‘We have been doing the best we can. We have got Inslee. Look at the progress,’” Rodgers said.

“But emissions don’t lie and the emissions keep rising.”

Cascadia’s Broken Promise

The official record shows that Rodgers and the youth litigants in all three jurisdictions are right at least about this: Washington, British Columbia and Oregon promised to significantly reduce their emissions of greenhouse gasses by 2020.

But they did not.

This happened even though renewable energy sources and other solutions are available. Technologically speaking, climate change is neither insurmountable nor unaffordable. It’s the politics that have fallen short.

Washington, Oregon and British Columbia — the heart of an eco-friendly region that’s frequently dubbed Cascadia — consider themselves a global leader on climate action.

The three governments set some of North America’s first mandates to reduce greenhouse gas emissions over a decade ago. And if any place on earth can show the world how to confront the climate crisis, it should be here. Cascadia’s abundant hydropower provides a head start toward living without fossil fuels, and the majority of voters in British Columbia, Washington and Oregon say they want to make that transition.

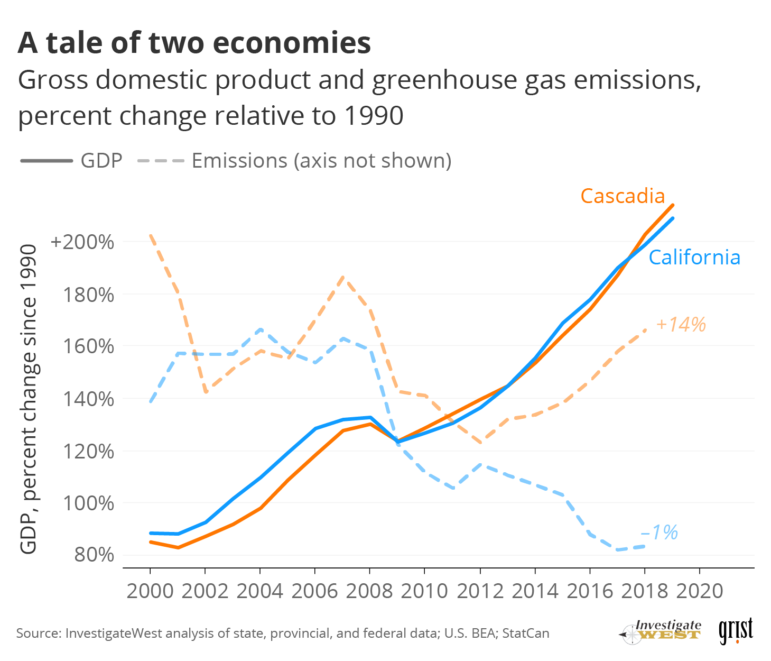

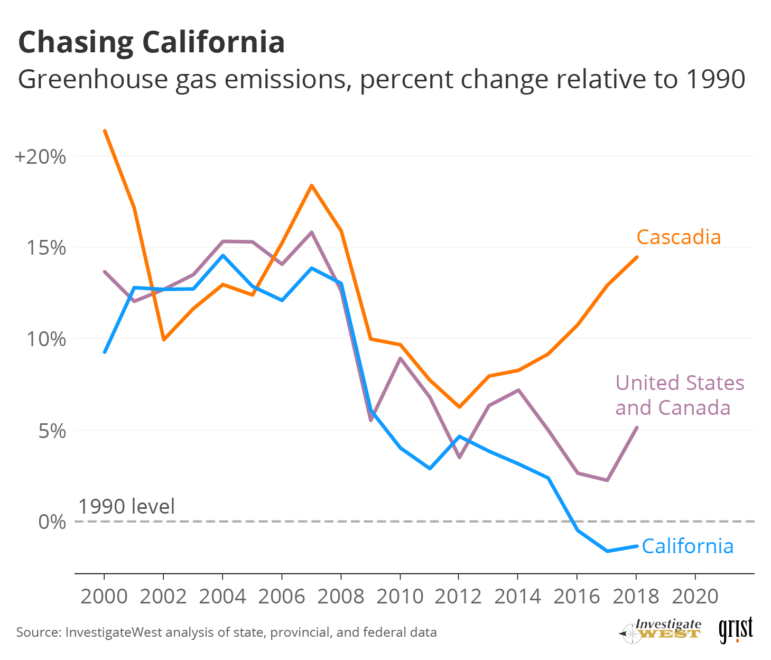

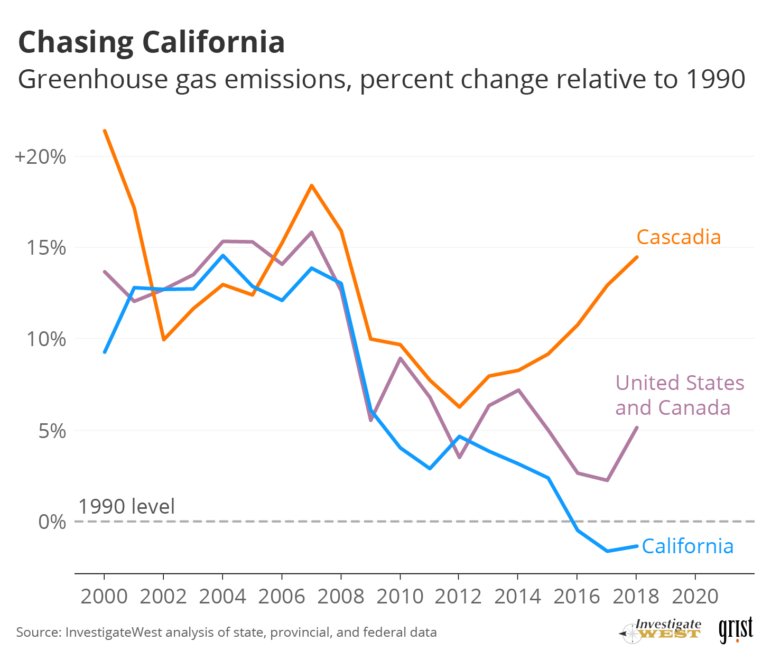

Yet Washington, B.C. and Oregon were not on track to meet their 2020 targets. In fact, until COVID-19 hit last year, emissions were rising. Between 2013 and 2018, the most recent five-year period for which Cascadia’s governments have completed counts, emissions rose by about 5%, 6% and 7% in Washington, Oregon and BC, respectively, according to a new analysis by InvestigateWest.

Over the same period, similarly fast-growing economies such as California and Germany released fewer of the greenhouse gas emissions that cause climate change. “I wouldn’t say we’ve done nothing. But there’s been an awful lot of dithering. We were supposed to do a whole hell of a lot better,” says KC Golden, who spent over a decade at Seattle-based think tank Climate Solutions and now serves on the board of international activist group 350.org.

In this May 15, 2019 photo, the Lower Granite Dam on the Snake River is seen from the air near Colfax, Washington. Cascadia’s bountiful electricity produced by hydropower dams like this one gives the region a head start on much of the globe on solving the climate crisis. Ted S. Warren/AP

BC’s trend paints a particularly stark picture. In 2018 it came within 0.1% of setting a new all-time emissions record for releases of greenhouse gases, according to InvestigateWest’s analysis, which adjusts the province’s official data to enable accurate comparisons with the U.S. figures. Over the five years prior, BC’s emissions grew more than five times faster than the Canadian average. And there could be more to come as its government fosters the province’s nascent liquified natural gas export industry.

Golden and other climate policy experts say measures to meet the climate goals set in 2007-2008 prevented some emissions, and may ultimately drive reductions. But they say Earth’s climate doesn’t give A’s for effort. As Golden puts it: “The atmosphere doesn’t care about anything but CO2 molecules how many molecules go into the atmosphere.”

Despite the dithering, Cascadia does have the solutions to climate change within its reach. The example set in California and modeling by Cascadia’s own planners show that renewable energy, electric vehicles and other solutions exist to get Cascadia off fossil fuels, slashing the carbon dioxide created by burning fossil gas, oil and coal, and the methane from leaked gas. In other words, Cascadia has the technology required to decarbonize .

Holding Earth’s warming to levels that avoid the worst effects of climate change demands faster reductions here, and everywhere. Global climate experts say that means halving global emissions by 2030. That requires a six-fold speed-up in renewable energy growth, for example, and a 12-fold speedup in electric vehicle sales, according to the World Resources Institute.

Clayton Aldern/Grist

So why is environmentally-conscious Cascadia stuck in first gear? The consensus answer from experts and activists interviewed by InvestigateWest: a shortage of political will. The region has been beset by partisan wrangling, fear of job losses, disagreements over how to ensure equity for already polluted and marginalized communities, and misinformation obscuring the full potential of well-documented solutions.

“The constraining factor has always been political feasibility, not economic feasibility,” says political economist and energy modeling expert Mark Jaccard, a professor at Simon Fraser University in Burnaby, BC, and a former chair of the British Columbia Utilities Commission.

The story of Cascadia’s decade of policy delay and emissions backsliding is a story of ambitious goals eroded by inertia. It’s a story of overestimating faith in economic logic and underestimating the enduring allure of economic growth. And, south of the 49th Parallel, it’s a tale of a bipartisan consensus split asunder, such that fighting for a cleaner future is seen, in some quarters, as an attack on freedom. Or worse.

Powering Down Coal

The imperative to transform fossil fuel-dependent energy systems took center stage around the world after the deadly destruction wrought by Hurricane Katrina in 2005 and the record heat of 2007, when Arctic sea ice melted to a fraction of its previous norms. Climate change was no longer just a future threat. It had arrived.

Cascadia lawmakers acted, mandating emissions reductions by 2020 and steeper cuts by 2050. As of 2008, Washington, BC and Oregon were among only four provinces and eight states to legally commit to decarbonization.

Oregon and BC set ambitious longterm goals of 75-77% reductions from their 1990 emissions, reflecting the global carbon cuts scientists believed were needed by mid-century to avert the worst of the impending climate disaster. Washington state came in with a relatively modest 50%-by-2050 goal reflecting what then-governor Christine Gregoire thought the state could guarantee.

Cascadia’s governments had experience with decarbonization. Hydropower continued to provide more than two-thirds of the region’s power thanks to a long legacy of leadership in energy efficiency. Since the 1970s, making customers more efficient had provided more “virtual” power capacity than actual generation from new power plants burning gas and coal.

All three governments chalked up quick wins in their power sectors.

Caithness Shepherds Flat windmills turn in Arlington, Oregon on March 17, 2014. The Shepherds Flat is the largest on shore windmill farm in the world, with 338 turbines. Meg Roussos/Bloomberg

BC immediately scrapped plans for a new gas-fired power plant and two coal generators. The province told its primary utility, provincially owned BC Hydro, to instead buy additional electricity from renewable energy projects such as wind farms and small-scale hydropower stations. Washington voters and Oregon’s legislature passed some of North America’s first requirements mandating privately owned utilities to add a rising share of wind, solar and other types of renewable power. That unleashed a boom in wind power development concentrated along the Columbia River Gorge, the natural wind tunnel that separates the states.

And guess what? It actually saved consumers money. Falling prices for wind and solar driven by innovation and scale made the mandates more economical.

Rural economic development made the mandates politically palatable. Jackie Dingfelder, a former member of the Oregon legislature who led passage of a package of climate bills in 2007, said representatives for rural counties saw renewable energy plants as a boost to declining tax revenues — one that panned out. “If you drive out in eastern Oregon and Washington you see tons of wind farms and those farmers get royalties and those communities get money,” said Dingfelder.

These power moves delivered for the atmosphere, particularly in Oregon. In 2007 coal provided over one-third of Oregon’s power. A decade later it was less than a quarter, and emissions from electricity consumption had declined by 27%.

Oregon also dialed in further reductions to come. In 2010 utility Portland General Electric cut a deal with environmentalists, codified by the legislature, to shut down Oregon’s only in-state coal-burning power plant. The utility got out of a $470-million retrofit of its air pollution controls, which would have extended the plant’s operating life to 2030 or beyond, by agreeing to shutter it in 2020.

Cascadia’s problem was the rest of its economy. Buildings, industry and especially transportation generate over two-thirds of Cascadia’s emissions. Carbon-cutting options for those — such as electric heat pumps to replace gas furnaces and urban redesigns to reduce vehicle travel — were more complex and costly than swapping out coal stacks for wind turbines. And none of Cascadia’s governments had policies strong enough to forcefully drive those options into use.

The closure of this coal-burning electrical plant near Boardman, Oregon, late last year will end emissions of about 2 million tons of carbon dioxide each year. The plant is owned by Portland General Electric, which aims to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions 80 percent by 2050. Photo courtesy of Portland General Electric

Greenhouse gas emissions — about four-fifths of which are carbon-based CO2 and methane from extraction and use of fossil fuels — fell for several years, thanks to cleaner electricity, as well as the global financial crisis of 2008. People traveled less, consumed less and produced less. Fossil fuel use dropped. Cascadia’s emissions fell by 8%. Then the economy rebounded. People moved more. Production and consumption rose. And carbon emissions came roaring back.

By 2018 robust economic growth across Cascadia had restored over four-fifths of the 19.5-megatons of annual emissions that the region shed during the downturn.

Reed Schuler, a senior advisor to Inslee on climate, told InvestigateWest that emissions rose because Washington’s economy is among North America’s fastest growing. “There’s more people living and working in buildings, more people driving around, more people flying around,” said Schuler.

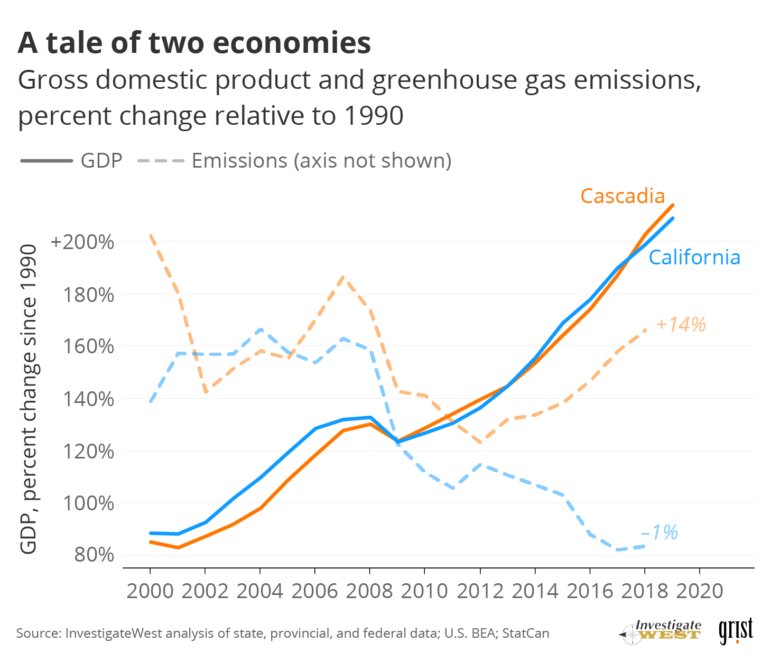

However, comparative analysis by InvestigateWest puts the blame squarely on Cascadia’s weak decarbonization policies. Between full economic recovery in 2012 and 2018, the most recent reporting year, California and Cascadia both booked a robust 26 percent increase in GDP. Over that period California drove its annual emissions down by more than 5 percent. Washington’s emissions —and Cascadia’s as a whole — ballooned by over 7 percent.

Clayton Aldern/Grist

Tracking Arnold

California “decoupled” economic growth from rising carbon via a raft of laws and policies that encouraged or mandated use of efficient products and cleaner energy. Many were legislated in 2006 under then-Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger, including the centerpiece: a scheme known as cap and trade . It set a cap on carbon emissions that declined annually, and enforced that cap by requiring polluters to buy credits — sold at auction — for every ton of carbon they released. By putting a price on carbon, cap and trade created a financial incentive to reduce pollution.

Cascadia’s governments all sought to match the breadth of California’s carbon-cutting policies. They sought to follow its harnessing of financial markets to drive down carbon emissions. They failed.

Early efforts in Washington and Oregon to enact cap-and-trade schemes fizzled. Washington approved a bill in 2008 that was later deemed unenforceable. Oregon ran out of time when the global economic meltdown struck that year, stoking economic anxiety. “The recession basically dashed that to the floor,” recalls Portland-based energy policy expert and climate activist Angus Duncan, then an advisor to the governor.

BC, in contrast, raced ahead. Like Schwarzenegger, then-Premier Gordon Campbell was a center-right politician who embraced climate action. BC’s parliamentary government, with its fewer checks on power than the U.S. system, enabled him to move fast — if he had his caucus behind him. In May 2007 Schwarzenegger visited Vancouver, signing a climate agreement and injecting star power into Campbell’s climate vision.

Clayton Aldern/Grist

By the end of the year Campbell had surmounted opposition within the province’s business community, and had a climate package in place. In May 2008 Campbell’s Liberal Party majority in the legislature formally approved North America’s first carbon tax . It took effect that July — five years before California’s more complex cap and trade system went into effect.

The tax started at C$10 (about US $7.77 today) per metric ton of CO2 emissions anticipated from every litre of gasoline, diesel and natural gas sold in BC. It was modest — adding just $1 or so to the price of a fill on a small car — but was set to increase annually to reach C$50 by 2020.

Within a few years economists were reporting small benefits and a reassuring lack of harms. The tax had trimmed fuel consumption in BC compared to other provinces in Canada while stimulating BC’s economy thanks to the government’s design for the revenues. BC returned its tax take by lowering income and business taxes and sending rebate checks to residents. The rebate checks protected lower-income residents from rising energy costs. Other measures protected energy-intensive, trade-exposed industries such as cement producers from being pushed out of the province.

Those measures could not, however, protect the tax and its champion from political attacks and misinformation. The province’s left-of-center New Democratic Party took the first swipe. During the 2009 election the NDP ran on an “Axe the Tax” platform, alleging that the carbon tax hurt working families. Campbell’s 20-point lead quickly evaporated.

When Campbell barely held on to his majority, arguments ensued as to whether the tax had nearly pulled him down or narrowly saved him by peeling environmental votes away from the NDP. But in 2011 Campbell’s Liberal party dumped him for a more populist leader. Premier Christy Clark took her lead from BC’s business lobbies — including fossil gas interests with large fracking operations in BC’s interior. She froze the carbon tax, rolled back funding for other climate measures, and rolled out a sales pitch for LNG investment.

So despite its early policy lead, BC’s decarbonization results proved worse than underwhelming. Instead of declining versus 2007, emissions rose through 2018.

Similar dynamics played out on Canada’s national stage, where Prime Minister Stephen Harper gained a majority in parliament in the 2009 election by attacking “job-killing carbon taxes” championed by his rival. Harper’s win kicked off a decade of Canadian climate inaction, including expansion of Alberta’s carbon-intensive oil sands. As Jaccard laments in his 2020 book The Citizen’s Guide to Climate Success, “Canada’s emissions went up rather than down.”

Steam rises from the Syncrude Canada Ltd. upgrader plant in this aerial photograph taken above the Athabasca oil sands near Fort McMurray, Alberta, Canada, on Monday, Sept. 10, 2018. Contributor/Bloomberg

The Price of Partisanship

To the south, hopes sprung high – but also tanked because of politics. Washington and Oregon governors returned to carbon pricing with their eyes on California’s cap-and-trade program rather than the political bloodbath up north. Alas, the same political crossfire leveled at BC’s tax — along with some novel attacks — would doom their carbon trading schemes in the state legislatures.

Inslee pushed carbon pricing after he became governor in 2013, in spite of Republican control of the state senate, where Sen. Doug Ericksen, an opponent of climate action whose district includes two refineries, chaired the environment committee. “It was ‘Into the valley of Death, Rode the six hundred’,” recalled Patrick Mazza, a longtime Seattle-based climate policy analyst and activist, evoking the Alfred Tennyson poem “The Charge of the Light Brigade” that immortalized an ill-fated 1854 cavalry charge in Crimea.

Inslee tried several times, and voters rejected two ballot measures, before Washington took a year off from carbon pricing battles in 2019.

Oregon governor Kate Brown led repeated charges over the same ground after she took office in 2015. Republican pushback there led to the strange events of June 2019, when Oregon state senators exited the capitol in Salem, denying Democrats the quorum they needed to outvote the Republicans.

On June 23, 2019 a reporter for The Wall Street Journal reached Oregon State Sen. Cliff Bentz by phone. From an undisclosed location in Idaho, Bentz admitted that he and his colleagues were “on the lam” — fugitives from a debate over cap-and-trade legislation advanced by the legislature’s Democratic leaders. Bentz had changed hotels twice over the past four days and secured a burner phone, after Gov. Brown ordered the Oregon State Police to find and return the wayward senators.

The senators’ run from lawmaking — a ruse they reprised last year — capped years of political dissolution that transformed an earlier consensus on climate action into open political warfare. In 2007 Oregon’s climate bills passed on bipartisan votes. In 2020, not one Republican would even cast a vote on a cap-and-trade measure backed by the state’s utilities.

Climate, said former legislator Dingfelder, is “right up there now with god and guns and abortion.”

Lower-income voters in Oregon and Washington understandably worry about new taxes and higher energy costs. Regressive tax systems in both states mean the lowest 20% of earners already pay the highest proportion of their income in taxes. Unions often paint carbon pricing as a job killer, in spite of contrary evidence from BC and California. Climate justice groups attack industries’ ability to buy rights to continue polluting the often minority, low-income communities nearby.

And then there’s the influence of corporations that sell fossil fuels or profit most when they are cheap. The sophisticated, well-financed Western States Petroleum Alliance has an especially strong record lobbying in Olympia, thanks to the state’s refineries, which provide over 4,800 jobs, most of which provide a healthy paycheck.

In Oregon, energy-intensive firms such as Koch Industries subsidiary Georgia-Pacific gave $117,619 in campaign donations over a decade to the 11 senators who skipped town, according to reporting by The Oregonian’s Rob Davis. The same firms gave $43,250 to the Democratic senators who stayed to vote.

Dingfelder sees Oregon’s vulnerability to ideology and misinformation as a legacy of decline in Cascadia’s long-standing forestry and mining industries. As well-paid resource jobs evaporated, some states such as California and Washington pivoted faster, investing in universities that then spun off new job creators such as Microsoft and Amazon.

“We were the poor stepchild,” she said. “A lot of people got left behind.”

Climate as Roadkill

As political backlash and game-playing blocked carbon pricing, Cascadia’s economies kept growing along the path of least resistance. In a world awash in cheap fossil fuels, that meant more carbon emissions. Especially from cars, trucks, trains and planes.

Transportation has long been Cascadia’s top climate challenge, accounting for nearly two-fifths of emissions by the time its economies rebounded from the global economic meltdown in 2012. Six years later vehicle emissions had ballooned by over 10% in Washington and Oregon and more than 29% in BC (in contrast California’s grew only 5% during that period.)

Cascadia’s transportation policies simply lacked the focus and strength to transform an inefficient system almost exclusively reliant on gasoline and diesel-fueled vehicles.

Fuel standards akin to California’s slowed emissions growth in Oregon and BC by requiring fuel suppliers, as a whole, to ratchet down the amount of fossil carbon per gallon in their gasoline and diesel. By 2018, BC’s law had prevented the release of over 9 million metric tons of carbon emissions — about as much as 2 million cars produce in a year, according to BC’s Ministry of Energy, Mines and Low Carbon Innovation. It cost consumers, at most, 12 cents per gallon, according to BC’s Utilities Commission.

But much of that reduction occu

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here